Transaction Specific Investments… click!… Sounds totally boring. But read on…

Transaction Specific Investments have been repeatedly proven to build trust in inter-organizational relationships.

Sometimes called Relationship Specific Investments (RSIs) or idiosyncratic investments, TSIs are unique investments that support the inter-organizational relationship and its performance.

Sometimes called Relationship Specific Investments (RSIs) or idiosyncratic investments, TSIs are unique investments that support the inter-organizational relationship and its performance.

They may be tangible or intangible but they are not easily transferable to other relationships and they lose their value if the relationship is terminated.

Examples of TSI include a joint marketing effort where the signage and promotional items are specific, a joint production facility or unique hardware, software and training.

From a purely calculative, somewhat negative perspective, TSIs are seen as a “deliberate strategy of locking oneself into a relationship, thus raising switching costs” if one partner choses to defect (Sako & Helper, 1998, p.393). They are referred to as “economic hostages” that control opportunism through economic incentives (Dyer & Singh, 1998).

Imagine you have a joint manufacturing facility – you won’t easily leave the partnership because the costs would be too high. Of course, this doesn’t mean the organizations trust one another – just that they have economic incentives to stay in the partnership. So TSIs alone are insufficient to build trust between organizations. What’s important, again, is how they are used.

TSIs build trust when they:

- Enhance coordination efforts between buyers and sellers to enable strategic outcomes (Jap, 1999.p.471)

- Offer a “credible commitment” They show that the vendor can be believed, cares for the relationship, and is willing to make sacrifices through such investments (Doney & Cannon, 1997; Ganesan, 1994; Geyskens et al., 1998; Sako & Helper, 1998; Zaheer & Venkatraman, 1995; ).

- Signal a long-term mutual commitment to the relationship which enhances trust, especially if both parties have other exchange alternatives (Ganesan, 1994; Sako & Helper, 1998; Zaheer & Venkatraman, 1995).

A long-term commitment and the expectation that your partner has taken your interests to heart are preconditions for serial equity to occur (Ganesan, 1994; McEvily et al.,2003, p.96). This means that reciprocity doesn’t have to occur immediately because the organization trusts that short term inequities will be corrected in the long-term (Ganesan, 1994; Sako & Helper, 1998; Poppo & Zenger, 2002).

Consistently, research finds that anticipated future longevity of a relationship is positively correlated to trust (Currall & Judge, 1995; Doney & Cannon, 1997; Ganesan, 1994; Sako & Helper,1998).

The length of your past relationship is not nearly as important as where you plan to go together in the future.

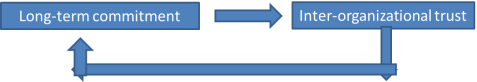

Remember how we determined that trust is generative in Week 2? A meta-analysis* by Geyskens et al. (1998) found that long-term orientation is a consequence of trust and that “the effect of trust on long-term orientation is even substantially larger than the direct effect of economic outcomes or any of the other antecedents” (p.242). So they influence and grow one another.

For best results: invest in your partners to signal long-term commitment and enhance outcomes. ( I believe this applies to professional development within organizations too!)

As we have seen in Part A and in Part B of Week 6, the use of formal governance mechanisms in IORs can either be seen as an imposition of power used to control the other party or it can be seen as a coordinating mechanism (Bachmann, 2006). When they focus on imposing power and control they erode trust (Kumar, 1996).

When formal governance mechanisms are used as a coordinating mechanism to provide role clarity, help to align interests, signal long-term commitment and provide a framework to support collaborative relationships, they build trust.

Have you seen examples of formal governance structures like hierarchy & monitoring, contracts and TSIs that build trust? Can you think of opportunities to use these formal mechanisms to enhance trust between departments or organizations?

*meta-analysis is a review of a large body of research to draw broader conclusions than you can obtain from a single study.