Experts believe that intangible assets like brand, client lists, reputation, etc. can be worth up to one-third of a company’s market value. Why?

A solid reputation acts as a shortcut to trust – a third party (individual or an organization) acts as a “proof source” or “proxy for trust” vouching for the credibility and goodwill of an organization which is the very definition of trust (Doney & Cannon, 1997; McEvily, Perrone & Zaheer, 2003).

Reputation can attract new partners, new or expanded opportunities, new employees and it can give an organization a chance to maneuver or redeem itself if an error is made.

In inter-organizational trust, reputation is about

- Benevolence/ Goodwill. The “extent to which firms and people in the industry believe a supplier is honest and concerned about its customers” (Doney & Cannon, 1997, p.37).

- Capability. The extent to which a firm follows “through on promises and commitments in the general supplier community” (Dyer and Chu, 2003, p.62)

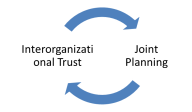

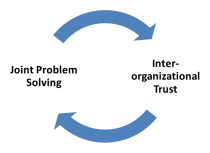

Trust and reputation are inseparable.

- Goodwill trust is a firm’s “reputation for dealing fairly and caring about its partner firm’s welfare in alliances (Das & Teng, 2001).

So what do your partners say about your organization? Are there opportunities to improve your goodwill trust or how you follow-through on promises and commitments?

How does reputation = trust ?

In Week 2 of Twelve Weeks to Trust, we looked at how trust moves from person to group to organization and vice versa.

This transfer of trust is what makes reputation such a powerful source of information and trust.

Potential partners determine trustworthiness through “trust transfer… rather than being based on direct experience with the object of trust [firm A], initial trust impressions are based on trust in a source other than the trustee” (McEvily, Perrone & Zaheer, 2003, p.94).

The trust source can be a previous partner organization, a third-party rating of Best Employers or Top Corporate Citizens, a trade association or a network.

Think about your business network – does it act as an information broker in your industry? Does your trade association create generally accepted norms of behaviour (Bhattacharya et al.,1998) ? Does your profession or field have “certain skills, level of competence, assets, and standards” (Das & Teng, 2001, p.275)? All of these form institutional trust to provide a minimum level of certainty that you will be a solid partner.

In case you think that cultivating a reputation for being trustworthy sounds “light” or Pollyana-ish, remember that firms guard their reputation out of calculated self-interest (Dasgupta, 1998; James, 2002). Firms are rewarded or penalized/ostracized for their behavior in the network of potential exchange partners (Axelrod, 1984; Bhattacharya et al., 1998; Das & Teng, 2001; Gulati, 1995; Hexmoor et al., 2006; Poppo & Zenger, 2002).

In their book Smart Trust, Stephen M.R. Covey and Greg Link use e-Bay as an example of how a seller’s bad reputation will turn off potential buyers and eventually lead to their expulsion from that market.

All things being equal, do you want to partner with an organization that has a stellar reputation or with one that can’t be trusted?

Don’t take my word for it. In the Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organization (a little light reading) Harvey James Sr. (2002) reviewed variations of prisoner’s dilemma games and concluded that :

“businesses that have a reputation for honest dealing will have decided advantages over those that do not have such a reputation” (James, 2002, p. 301).

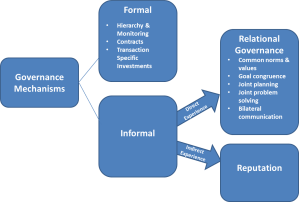

The benefits of a reputation for inter-organizational trustworthiness include:

- Improved performance (Dyer & Chu, 2003)

- Greater credibility trust (Ganesan, 1994)

- Greater relational governance, i.e., trust, with a specific buyer (Claro et al., 2003).

- Lower search costs for a partner

- Lower initial governance costs due to pre-existing trust (Gulati, 1995)

In a broader context, an organization’s reputation itself channels behaviours of, and towards, the organization in certain directions – staff behave the way the culture & reputation expects them to behave and potential partners, expecting trustworthiness, will engage in the relationship with a greater propensity to trust, more openness and less suspicion. This makes the future behaviour of the organization and their (potential) business partners more predictable, which is an important element of trustworthiness (Bachmann & Inkpen, 2011).

Yes. Reputation is a powerful mechanism for trust building. However, one note of caution on its predictive value. While reputation is used widely and is generally reliable as a proxy for trust based on direct experience – especially when it is backed up by training, certifications, past results, etc. – it is based on past actions and is not always an accurate future predictor.

In the Journal of Business Ethics (2003), Keith Blois of Oxford University examined how a changing economic context changed the way British retailer Marks & Spencer’s dealt with suppliers with whom it had enduring relationships and where deep trust existed. In his piece, Blois warns that:

Reputation cannot always predict how the other party will act in the future because contingencies cannot always be expected (Blois, 2003). He points out the important distinction between reputation built on past behaviours and trust as an expectation of future behaviour and recommends that organizations “trust but question”.

Finally, when we talk about an organization’s reputation we immediately understand the importance of the salespeople, the front-line staff or ambassadors in upholding it. That interplay between inter-personal and inter-organizational trust is our topic for Week 9 of Twelve Weeks to Trust.